|

|

|

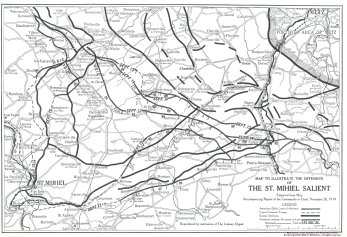

Salient is the military term for the very common words "pocket" and "wedge." The St. Mihiel salient, the elimination of which was the first big, concerted, offensive operation of our forces in large number in France, was a deep pocket driven into the French lines in the fall of 1914 by the German armies in their attempt to outflank Verdun, whose forts held the key to the defense of Eastern France. The right edge of this wedge, as a glance at the map will show, was just above Pont-a-Mousson, while the left edge was at Les Eparges, a few miles southeast of Verdun.

This pocket, always the deepest and sharpest on the western front, was some 18 miles across from base to base, and slightly over 13 miles in depth. Yet measuring around its perimeter, it was no less than 40 miles in extent. To pinch off or close the salient meant shortening the line about 22 miles.

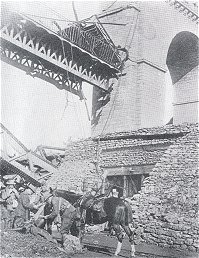

[Photo

at right - "At St. Mihiel: A Yankee machine gun company passing

through the ruins of a village leveled by artillery fire in the St. Mihiel

salient."] There were other considerations than the

decrease in battle front which caused General Pershing

to select this as the sector of attack of the First America Army. For

four years this pocket had been a threat to Verdun, about which the Germans

had closed on the northern and eastern side. If the left side of

the wedge above St. Mihiel was driven still farther westward, Verdun would

be virtually cut off and the French forces therein surrounded and captured.

Furthermore, the German advance at the deepest point of the pocket

barely cut the main railroad from Paris to Verdun, Toul, Epinal and Belfort,

a double-track line that linked up the great fortresses of Eastern France.

This had been a great loss, for it interfered with the speedy movements

of troops from one sector to another of the southern battle front. It

had been necessary for four years to transport troops by a single track

line farther south, much longer and burdened with all traffic to Toul

and Nancy.

[Photo

at right - "At St. Mihiel: A Yankee machine gun company passing

through the ruins of a village leveled by artillery fire in the St. Mihiel

salient."] There were other considerations than the

decrease in battle front which caused General Pershing

to select this as the sector of attack of the First America Army. For

four years this pocket had been a threat to Verdun, about which the Germans

had closed on the northern and eastern side. If the left side of

the wedge above St. Mihiel was driven still farther westward, Verdun would

be virtually cut off and the French forces therein surrounded and captured.

Furthermore, the German advance at the deepest point of the pocket

barely cut the main railroad from Paris to Verdun, Toul, Epinal and Belfort,

a double-track line that linked up the great fortresses of Eastern France.

This had been a great loss, for it interfered with the speedy movements

of troops from one sector to another of the southern battle front. It

had been necessary for four years to transport troops by a single track

line farther south, much longer and burdened with all traffic to Toul

and Nancy.

As an offensive stroke, the closing of the St. Mihiel salient was fraught with equally great possibilities. It meant the restoration of about 150 miles of French territory, which was under the yoke of its German oppressors; the reversal from a threat to surround Verdun to a very decided menace of an allied attack upon Metz, the left hinge and base of the German battle line; the establishment of a straight base line from which attacks could be launched toward Conflans at the coal and iron fields of Briey and Longwy, the German mineral basins, and at the great railroad arteries through Sedan, Montmedy and Metz.

Several desperate attempts had been made by the French earlier in the war to straighten out their lines and relieve the pressure on Verdun. In the spring of 1915, they struck a hard blow with large numbers at Les Eparges on the western flank. The attack was continued several weeks and both sides left thousands of dead on the field of battle. The Germans were estimated to have lost 30,000 killed in this series of operations, while the French casualties were even heavier. Outside of local gains, the attack was unsuccessful. The French resumed their drive in the summer on the other side of the pocket at Apremont, attempting to crush in that flank. The fighting was bitter and the French made some headway; but all was lost in a counter-offensive of the Germans in the fall of 1915. After that nothing was done on either side for three years, as the tide of active operations shifted to other sectors. Both sides improved their defensive fortifications, but neither assumed the offensive. The lines were held by divisions that needed rest and recuperation from operations elsewhere.

The military strategy employed by General Pershing in the reduction of this salient is explained very well by a homely illustration. Pont-a-Mousson and Les Eparges, the bases of the pocket, were the hinges of two great doors which opened outward in the direction of St. Mihiel. If the doors were swung together on these hinges, they would meet just north of Vigneulles and form a straight line. To accomplish this, it was necessary for the divisions on the left flank to work eastward, while those on the right side made their way northwesterly to join them. The attacks had to be so timed that the flanks would arrive at the junction point at the same time. It was necessary also that the maneuver be accomplished quickly to cut off the German forces at the bottom of the pocket and prevent their escape.

[Photo

at right - "The Bridge at St. Mihiel: This dugout, in the shadow

of a wrecked railway bridge, at Flirey, quartered Yankee officers."]

For the successful execution of this operation, General

Pershing withdrew from the Marne salient the eight divisions,

which were engaged there in the hot fighting of June and July, 1918; brought

from other quiet sectors several divisions which were receiving their

training in trench warfare; and transported clear across France from their

training camps still other divisions which had had no actual battle experience.

The organization of the First American Army and the commencement of assembly

of all the units that were to take part in the attack began August 10.

The plans of the general staff provided for the concentration of

about 600,000 troops of all arms and branches, together with their weapons

and material, for the operation. As it was planned as a surprise,

all movements were conducted by night. No troops or signs of unusual

activity were visible on the roads by day. But with the fall of

night, all highways were jammed with trucks, guns, ammunition, tanks,

and wagons, going forward in position for the drive. The front line

trenches were held lightly so that the enemy might not suspect the blow

that was being aimed at him. Complete success depended upon overwhelming

him before he could adequately man with his reserves the powerful defensive

fortifications he had built.

[Photo

at right - "The Bridge at St. Mihiel: This dugout, in the shadow

of a wrecked railway bridge, at Flirey, quartered Yankee officers."]

For the successful execution of this operation, General

Pershing withdrew from the Marne salient the eight divisions,

which were engaged there in the hot fighting of June and July, 1918; brought

from other quiet sectors several divisions which were receiving their

training in trench warfare; and transported clear across France from their

training camps still other divisions which had had no actual battle experience.

The organization of the First American Army and the commencement of assembly

of all the units that were to take part in the attack began August 10.

The plans of the general staff provided for the concentration of

about 600,000 troops of all arms and branches, together with their weapons

and material, for the operation. As it was planned as a surprise,

all movements were conducted by night. No troops or signs of unusual

activity were visible on the roads by day. But with the fall of

night, all highways were jammed with trucks, guns, ammunition, tanks,

and wagons, going forward in position for the drive. The front line

trenches were held lightly so that the enemy might not suspect the blow

that was being aimed at him. Complete success depended upon overwhelming

him before he could adequately man with his reserves the powerful defensive

fortifications he had built.

The moral and psychological value of the operation's success was almost as great as the military advantages to be obtained. While the American divisions had fought splendidly when brigaded with the British and French, they had conducted no offensive on their own initiative and under their own leadership. The elimination of the salient would be the acid test of their offensive ability, while the successful execution of a task at which the French had failed for four years would not only inspire respect and courage in our allies as well as strike terror in the hearts of the Germans, but the American people would be aroused to the highest pitch of enthusiasm by an action in which our fresh, vigorous troops were pitted successfully against their much vaunted German foes.

The plans of the attack were worked out to the minutest detail by the army staff. The hour and minute at which the barrages were to be laid down, the rate of advance of the infantry behind them, the sector of attack of each division, the objectives of each day's fighting were mapped out carefully in advance, and all commanders, from division down to platoon leaders, were rehearsed on the parts assigned to each. Special stress was laid upon the effective cooperation of all arms, infantry, artillery, aviation, tanks, machine guns, engineers and supply trains. The French were of very great assistance, for in addition to loaning us much artillery, many of their best bombing and scout planes, and all of the tanks that were used in the attack, they contributed three divisions for the very delicate operations against the German troops at the nose of the salient.

[Photo

at right - "The First Day at St. Mihiel: Temporary trenches

dug by Americans on the first night of the St. Mihiel drive, near Beney,

Meuse."] The infantry of nine American divisions was

assigned to make the attack on the two flanks of the pocket, crush them

in by frontal assaults, close to the center, and capture the garrison

of several thousand men at its bottom. On the right flank, strung

from Pont-a-Mousson as a pivot, was the First Corps, commanded by General

Liggett, and composed of the 82nd, 90th, 5th and 2nd divisions.

General Dickman commanded the Fourth Corps, made

up of the 89th, 42nd and 1st divisions, which were stationed in the center

of attack and upon the left of the First Corps. Upon the left of

the Fourth Corps, and strung lightly around the tip of the salient from

Xivray to Mouilly, was the Second French Corps, while the western base

of the wedge was held by the Fifth American Corps, under General

Cameron, made up of the 26th and 4th American divisions and a

French division. In reserve for the three American Corps were the

3rd, 35th, 78th and 91st divisions, while the 33rd and 80th were available

in case of need.

[Photo

at right - "The First Day at St. Mihiel: Temporary trenches

dug by Americans on the first night of the St. Mihiel drive, near Beney,

Meuse."] The infantry of nine American divisions was

assigned to make the attack on the two flanks of the pocket, crush them

in by frontal assaults, close to the center, and capture the garrison

of several thousand men at its bottom. On the right flank, strung

from Pont-a-Mousson as a pivot, was the First Corps, commanded by General

Liggett, and composed of the 82nd, 90th, 5th and 2nd divisions.

General Dickman commanded the Fourth Corps, made

up of the 89th, 42nd and 1st divisions, which were stationed in the center

of attack and upon the left of the First Corps. Upon the left of

the Fourth Corps, and strung lightly around the tip of the salient from

Xivray to Mouilly, was the Second French Corps, while the western base

of the wedge was held by the Fifth American Corps, under General

Cameron, made up of the 26th and 4th American divisions and a

French division. In reserve for the three American Corps were the

3rd, 35th, 78th and 91st divisions, while the 33rd and 80th were available

in case of need.

The artillery concentration for the attack was one of the greatest of the entire war. Guns were so numerous that they seemed placed behind every particle of cover available. They were greatly out of proportion to the amount of infantry used. Their number was about 2,000, while their calibers ranged from the famous French 75's up to three huge American naval guns, which had a range of about 20 miles and which bombarded the German lines of communication far in the rear of the battle lines. All calibers were supplied lavishly with ammunition to batten down the strong natural and artificial defenses, which the enemy had erected in front of him in the four years of his occupation of this sector.

Of the 600,000 men assembled for the drive, about 250,000, twice the size of any American army ever engaged in one battle, were employed actively in the operations. The rest were kept in reserve or used in the service of supply to the combat troops. Against them were opposed seven German divisions in the line and four in reserve. However, though they were considerably inferior in numbers as compared with the attacking forces, a much smaller force was necessary to defend the salient than to attack it. They were powerfully supplied with the most potent weapons of defense, an abundance of all calibers of artillery and of light and heavy machine guns.

The Germans, in spite of the secrecy that was maintained in the preparations for the attack, seem to have had some inkling of its coming. Their plans, according to documents captured from prisoners, appear to have vacillated. Some of the heavy artillery was withdrawn to the second line of defense, known as the Michel position, and all work on fortifications was stopped a few days before the blow fell. No extra reserve divisions were brought into the sector for a more powerful defense. This was due probably to the fact that they were needed worse at other parts of the front to stem the French and English drives which were in progress. However, it has been established very clearly that the Germans did not evacuate the salient "according to previous plans," as the German war office announced after the battle to soften the bitterness of the losses in men, guns, and ground.

The attack started with a tremendous artillery preparation at 1 o'clock on the morning of September 12. The chorus of two thousand guns, majestic in their roar, lighting up the pitch black darkness of a rainy night with splotches like rays of lightning, and fairly shaking heaven and earth with their tremendous power, played for four hours upon the towns, shelters, and strong points of the enemy in the rear of their front lines and made the night for them a veritable inferno. At five o'clock sharp, all firing ceased and an unearthly calm pervaded everything for a half hour. Then all burst forth again in a mighty roar as a barrage of high explosive shell was laid down upon the front lines of the Germans. Our infantry, jumping out of their trenches in the fog and mist of the early morning, leaped forward through the tangle of barbed wire to the attack. They found the Germans huddled in groups in their dugouts or torn and mangled by the hurricane of shell and shrapnel. Some put up a sturdy resistance, others, bewildered and nerveless, gave themselves up with little fighting. The American troops, inspired by the success they attained in the first few hours of the fighting, pressed forward vigorously on the flanks of the pocket, while the French, with great skill, engaged the enemy at the bottom of the salient and prevented his retreat. The advance continued throughout the day and night of September 12, and early on the morning of September 13, the advance guards of the 1st and 26th Divisions met, as had been planned, just north of Vigneulles, where the doors of the wedge were to be closed.

Every objective of the commander-in-chief was attained and, during the course of the next two days, the line was straightened from Les Eparges to Pont-a-Mousson. The prisoners taken in the engagement numbered about 16,000, while the guns counted 443. These figures do not include a large number of machine guns and a great mass of materials and stores, which the Germans were forced to abandon in their haste to escape.

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Military Page ]

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Main Page ]

Except as noted, all HTML code and graphics in the URL path [http://www.knoxcotn.org/military/wwi/] were created by and copyrighted 2001-2003 to Billie R. McNamara. All rights reserved. Please direct all questions and comments to Ms. McNamara.This page was last updated January 2, 2004. Visitor