Our Navy in the War

|

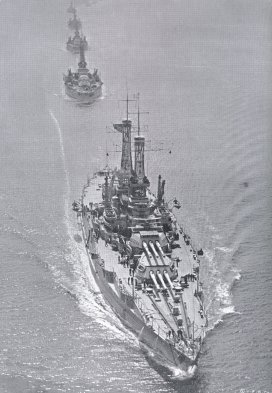

| Our Fleet at Sea The battleships and cruisers that stood guard with British in North Sea to prevent escape of German fleet. |

The hundreds of Knox Countians, who cast their lot with the navy and went to sea during the world war, made the same splendid record and wrote as glorious a page in local history as their brothers who chose the army and fought the Huns on land. They ably upheld the traditions established a half century ago by Farragut and Maynard as the guardians of our flag upon the trackless paths of the ocean. Theirs was not so spectacular a task, nor did they receive the publicity and prominence which other branches of the service did. Yet the two million soldiers, who sailed to France under the convoy of our fleet, know the relentless vigil and the hourly peril that the men of the navy underwent that our armies, with the food and equipment for them, might reach the battle line in safety.

For nineteen months they braved the dangers of the sea upon battleships and cruisers, submarines and merchantmen. They stood guard with the English at the mouth of the Kiel Canal to await the appearance of the German fleet for battle, they hunted the seas upon destroyers and chasers to ferret out the hostile submarines, they manned the transport vessels that plied the Atlantic in transporting our troops to France. There was little relief or rest for them, for their vessels were at sea the great majority of the time. They were ever under the shadow of death from the monsters that lurked beneath the waters.

The

navy was the one department of our government which was ready for action

when war was declared. Within a few hours after the passage of the

war resolution, Admiral Sims was gathering a fleet of

destroyers and preparing to sail for Queenstown, England. In less

than a month they were on guard duty in European waters. It is worthy

of more than passing comment that in all the criticism and vituperation,

which flooded the nation in its mad frenzy to get ready adequately for

the war, and in the series of investigations which followed its close,

there was never any abuse or evil said of the navy. It went through

the trying period without scandal or investigation. Its efficiency

was so thorough that no partisan or political attack was made upon it.

The

navy was the one department of our government which was ready for action

when war was declared. Within a few hours after the passage of the

war resolution, Admiral Sims was gathering a fleet of

destroyers and preparing to sail for Queenstown, England. In less

than a month they were on guard duty in European waters. It is worthy

of more than passing comment that in all the criticism and vituperation,

which flooded the nation in its mad frenzy to get ready adequately for

the war, and in the series of investigations which followed its close,

there was never any abuse or evil said of the navy. It went through

the trying period without scandal or investigation. Its efficiency

was so thorough that no partisan or political attack was made upon it.

[Photo at right - "Return of Our Victory Fleet: American dreadnaughts, returning from European waters, sailed up the New York harbor in battle formation in April, 1919."] Of the varied work which our navy did during the war, perhaps the greatest and most effectual was in the convoy and transportation of troops and supplies to Europe. While the English merchant marine gave great assistance by furnishing the vessels for a great deal of this work, the larger part of it was done by our own navy. This was work of the most vital nature, for the cries and pleas of our allies for more, more men in the spring and summer of 1918 were insistent. Defeat stared them in the face unless they had more divisions to check the German onslaughts. Every sea-going vessel that our government owned, which was not absolutely needed in some other phase of work, was manned by the men of the navy and put into the transportation service.

The convoy system, which was worked out as a means of avoiding the heavy losses of the British, who sent out ships alone upon the sea to become the prey of the submarines, consisted of collecting several troop or cargo vessels into a group, sailing from the same port at the same time. There were usually a dozen or more of these craft which put to sea as a unit, and which followed a well known lane across the ocean. Cruisers and the older battleships protected them from German raiders, while a flotilla of destroyers met them when they entered the danger zone and guarded them against submarine attack. If the submarines dared to appear in their midst, the transports scattered to avoid making themselves targets, but the fighting craft attacked with guns and depth bombs. After several encounters, in which they learned the system of defense that had been adopted, the submarines became more wary of attack upon these groups and confined their attention more and more to unprotected vessels on the high seas. The fear, which swept over the American people at the beginning of the war because of the submarine terror, gradually subsided as every transport vessel bound for France with troops arrived there in safety.

That not a single ship of the hundreds, which transported two million men to France, was torpedoed while eastward bound, and that only three -- the President Lincoln, the Antilles, and the Covington -- were sunk on return trips to America, is eloquent proof of the success of the convoy system and of the vigilance exerted by our cruisers and destroyers against would-be attackers. The submarine peril, which reached its apex about the time this nation entered the war, steadily declined thereafter. Our own losses at sea were insignificant in proportion to the amount of tonnage that was exposed in the nineteen months of our participation in the war to the attacks of the submarines. While complete figures are not available, statistics for several months indicate that the sinkings of all American vessels by mines and torpedoes were somewhat less than one per cent of our tonnage.

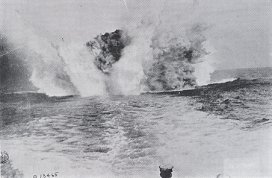

[Photo

at left - "The Depth Bomb: Explosion of a 300-pound anti-submarine

charge, fired from the U. S. S. Whipple."]

While a part of our fleet was guarding transport and cargo vessels, the

rest of it was waging an active, offensive warfare on the submarines upon

the high seas and around the channel ports, standing guard with the British

fleet at the mouth of the Kiel Canal, planting mines in the strategic

areas in the North or Mediterranean Seas, or patrolling our long coast

line against hostile attacks. Only three fighting ships were lost

as a result of enemy action. They were the Alcedo, a converted

yacht; the Jacob Jones, a converted torpedo boat destroyer; and

the San Diego, a cruiser. None of the larger and heavier

battle ships were injured.

[Photo

at left - "The Depth Bomb: Explosion of a 300-pound anti-submarine

charge, fired from the U. S. S. Whipple."]

While a part of our fleet was guarding transport and cargo vessels, the

rest of it was waging an active, offensive warfare on the submarines upon

the high seas and around the channel ports, standing guard with the British

fleet at the mouth of the Kiel Canal, planting mines in the strategic

areas in the North or Mediterranean Seas, or patrolling our long coast

line against hostile attacks. Only three fighting ships were lost

as a result of enemy action. They were the Alcedo, a converted

yacht; the Jacob Jones, a converted torpedo boat destroyer; and

the San Diego, a cruiser. None of the larger and heavier

battle ships were injured.

Some

of the most effective, as well as the most dangerous work done by our

navy was in the laying of mines. These made a great barrier against

the escape of the German fleet and the slipping out of an occasional raider

to prey upon commerce. The seas between Norway and Scotland, which

were the main outlet, were planted with thousands of mines by special

mine layers. To the south, the American navy had another force of

vessels which cooperated with the British in sweeping the English Channel

of these menaces to the safety of transport ships. [Photo

at right - "Depth Charges: Anti-submarine bombs loaded on the

destroyer, Stockton, for use against the 'Huns'."]

Some

of the most effective, as well as the most dangerous work done by our

navy was in the laying of mines. These made a great barrier against

the escape of the German fleet and the slipping out of an occasional raider

to prey upon commerce. The seas between Norway and Scotland, which

were the main outlet, were planted with thousands of mines by special

mine layers. To the south, the American navy had another force of

vessels which cooperated with the British in sweeping the English Channel

of these menaces to the safety of transport ships. [Photo

at right - "Depth Charges: Anti-submarine bombs loaded on the

destroyer, Stockton, for use against the 'Huns'."]

On land the navy's activities were not inconsiderable. No unit or branch of the service showed greater bravery or won more laurels during the war than the men of the marine corps. Their deeds at Belleau Woods, Bouresches, Soissons, St. Mihiel and in the Argonne Forest have been told in song and story. The personnel of this peculiar branch of the navy, which is trained for both land and sea duty, was of the very highest. They proved their valor on field after field of battle. Their defense of Belleau Woods is one of the epics of the war. Of the eight thousand who were picked for service in France, more than a half were killed or wounded.

The most notable need of our army in France was artillery. The French furnished General Pershing with the lighter calibers, but there was a deficiency of heavy, long range guns. The ordnance department of the navy came to the rescue by designing and constructing a battery of 14-inch rifles, shipping them across the seas on special mounts, and transporting them across France to the American front on special cars. They threw a projectile weighing 1400 pounds and had a range of about 20 miles. They were used with great effect in bombarding towns and strong points far in the rear of the German lines. Their military effect was far superior to that of the German "Big Berthas," which terrified Paris. In spite of their tremendous size and weight, they were thoroughly mobile and capable of being moved on short notice to other parts of the front.

In the execution of the innumerable demands made upon it by the requirements of the war, the navy underwent an expansion and growth almost in proportion to that of the army. The number of officers was increased from 4,376 to 10,409, the enlisted personnel from 62,667 to 216,968. The men and officers, who were members of the naval reserve in time of peace, also were called to active duty during the war. The number of officers was enlarged from 877 to 21,622, while the personnel of the enlisted men was raised to 289,639, of whom about 8,000 were women.

[Photo

at left - "A Sub-Destroyer: Notice the camouflaged color to

prevent observation." Photo at right - "A Sub-Chaser:

This type of boat was a terror to enemy submarines."]

At the close of the war, our navy had 40 battleships of the first-class,

32 cruisers, 125 destroyers, 17 torpedo boats, 68 submarines, 303 submarine

chasers, 79 mine planters and sweepers, 56 yachts on patrol duty, 33 gunboats,

8 monitors, and a few other ships used for special duties. Furthermore,

our navy was manning 50 troop transports, 230 cargo transports, 50 patrol

vessels, and 175 barges. The total number of ships operated at the

end of the war was about 2,000, as compared with 250 when the war begun.

[Photo

at left - "A Sub-Destroyer: Notice the camouflaged color to

prevent observation." Photo at right - "A Sub-Chaser:

This type of boat was a terror to enemy submarines."]

At the close of the war, our navy had 40 battleships of the first-class,

32 cruisers, 125 destroyers, 17 torpedo boats, 68 submarines, 303 submarine

chasers, 79 mine planters and sweepers, 56 yachts on patrol duty, 33 gunboats,

8 monitors, and a few other ships used for special duties. Furthermore,

our navy was manning 50 troop transports, 230 cargo transports, 50 patrol

vessels, and 175 barges. The total number of ships operated at the

end of the war was about 2,000, as compared with 250 when the war begun.

Our navy had moved from third into second place among the naval powers of the world, displacing Germany and ranking next to England. With the addition made in the few months following the war as the result of construction begun before that time, the gap that separated us in naval strength from first place upon the seas was cut down materially.

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Military Page ]

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Main Page ]

Except as noted, all HTML code and graphics in the URL path [http://www.knoxcotn.org/military/wwi/] were created by and copyrighted 2001-2003 to Billie R. McNamara. All rights reserved. Please direct all questions and comments to Ms. McNamara.This page was last updated January 2, 2004. Visitor