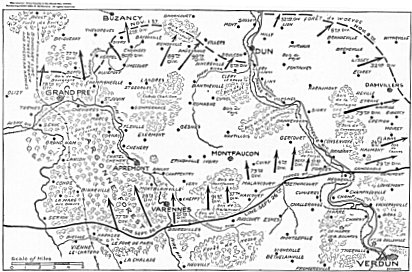

Of all the battles and engagements in which Knox Countians took part during the world war, more men and officers of them were engaged perhaps, first and last, in the 47-day struggle of the American army against the vital German positions in the Argonne Forest northward as far as Sedan than in any other large conflict or large operation in France. As has been pointed out in a previous chapter, these Knox Countians were not grouped into one combat unit, but were scattered through many organizations. They were to be found in the Fifty-fifth Field Artillery Brigade, the Second Corps Artillery Park, the Forty-second Division, the Eighty-first and Eighty-second Divisions, the marines, the five regular divisions and many of the other army corps, and divisional units that participated in this long campaign.

The Meuse-Argonne offensive should be regarded as a campaign, a series of battles, rather than a single engagement. It was a prolonged struggle of almost seven weeks between two great armies, engaged in a death grapple at the most vital part of a battle line more than 400 miles long. No better illustration of the extreme importance, with which the German high command regarded the Argonne sector, can be found than in the manner in which its armies were disposed in the crucial months of October and November, 1918. Before the British and French troops the German armies were withdrawn as swiftly as possible, and only rear-guard actions took place. Against the American forces, however, they resisted to the last inch with the best troops they had, knowing that if General Pershing reached his objective at Sedan, their whole line of communication on the Western Front would be pierced and the divisions against the French and English would be in danger of being flanked and cut off.

The

plans for the attack were laid some weeks before it actually began. Toward

the latter part of July or the first of August, 1918, when the success

of the allied counter-offensive was assured and the offensive was definitely

wrested from the German high command, Marshal Foch and

General Pershing agreed upon the plan of action that

the American armies should pursue on the eastern end of the battle front.

First, the St. Mihiel salient was to be reduced; second, the German

positions in the Argonne Forest and along the Meuse River were to be taken

by frontal assault; third, the American and French armies were then to

outflank and capture Metz, seizing the coal and iron fields of Longwy

and Briey. If these operations were successful, the only tenable

position for the enemy would be the east bank of the Rhine on German soil.

The

plans for the attack were laid some weeks before it actually began. Toward

the latter part of July or the first of August, 1918, when the success

of the allied counter-offensive was assured and the offensive was definitely

wrested from the German high command, Marshal Foch and

General Pershing agreed upon the plan of action that

the American armies should pursue on the eastern end of the battle front.

First, the St. Mihiel salient was to be reduced; second, the German

positions in the Argonne Forest and along the Meuse River were to be taken

by frontal assault; third, the American and French armies were then to

outflank and capture Metz, seizing the coal and iron fields of Longwy

and Briey. If these operations were successful, the only tenable

position for the enemy would be the east bank of the Rhine on German soil.

The first step was a complete success, although, if certain well authenticated rumors are correct, it was made against the wishes of Marshal Foch, who toward the latter part of August came to the opinion that this pocket could not be wiped out in time for the American divisions to reach the Argonne Forest and make adequate preparation within two weeks for such a great attack. The will of General Pershing prevailed, however, and his knowledge of the capabilities of his divisions was more than justified by events.

The German defenses from the Meuse to the Argonne were the most formidable on the western front. They were both natural and artificial. The natural defenses were a long series of heights and ridges, wooded and covered with brush, bushes, and strong points. Upon these the Germans had built successive lines of artificial defenses, the Hindenburg Line, the Hagen Stellung, the Volker Stellung, the Kriemhilde Stellung, and the Freya Stellung. Concrete machine gun and artillery emplacements, several closely woven barbed wire systems, mines and booby traps, and an intricate system of interlocking trenches added further strength to these natural fortifications, which guarded the great railroad system in their rear, the coal mines of Northern France and Belgium, and the iron mines of Lorraine.

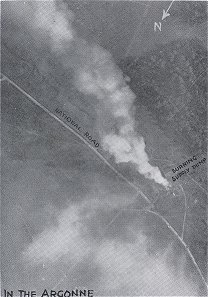

[Photo

at right - "A Direct Hit: An American aeroplane bomb landed

squarely on this German supply dump."] The plan of battle

called for the American army to attack from Vienne-le-Chateau, on the

eastern border of the Argonne Forest, to the west bank of the Meuse River.

A French army was to drive forward at the same time on the west

side of the Argonne, thus creating two deep salients on both sides of

the forest, which would cause the evacuation of its matted, tangled woods

by the Germans therein. Nine infantry divisions -- the 77th, 28th,

35th, 91st, 37th, 79th, 4th, 80th, and 33rd, arranged in order from left

to right -- were used by General Pershing to make the

assault. They were supported by a tremendous concentration of American

and French artillery of all calibers. The total number of guns employed

in the preliminary bombardment, which began at 2:30 o'clock on the morning

of September 26, was about 4,000. They fired more than 300,000 shells

that day, a volume of shell and shrapnel and fire that no human force

could resist on such a front. They withered and blasted all first

line defenses in front of them, and made the early morning hours a living

hell for the Germans, protected though they were by almost impregnable

defenses.

[Photo

at right - "A Direct Hit: An American aeroplane bomb landed

squarely on this German supply dump."] The plan of battle

called for the American army to attack from Vienne-le-Chateau, on the

eastern border of the Argonne Forest, to the west bank of the Meuse River.

A French army was to drive forward at the same time on the west

side of the Argonne, thus creating two deep salients on both sides of

the forest, which would cause the evacuation of its matted, tangled woods

by the Germans therein. Nine infantry divisions -- the 77th, 28th,

35th, 91st, 37th, 79th, 4th, 80th, and 33rd, arranged in order from left

to right -- were used by General Pershing to make the

assault. They were supported by a tremendous concentration of American

and French artillery of all calibers. The total number of guns employed

in the preliminary bombardment, which began at 2:30 o'clock on the morning

of September 26, was about 4,000. They fired more than 300,000 shells

that day, a volume of shell and shrapnel and fire that no human force

could resist on such a front. They withered and blasted all first

line defenses in front of them, and made the early morning hours a living

hell for the Germans, protected though they were by almost impregnable

defenses.

In spite of this bombardment, the infantry, who leaped out of their trenches and went over the top at 5:30 a.m. behind a smoke and shell barrage, had great difficulties from the German machine gun fire. They were cut and slashed by the hostile gunners, hidden behind trenches, logs, up in trees, or behind any kind of protective cover. The advance was almost wholly through woods. Yet the progress on the first day was very satisfactory, for the German line was penetrated at some places to a depth of six or seven miles. Montfaucon, the highest point in the sector, was entered and definitely captured the following day. Most of the divisions reached their objectives. The attack was followed up the next day, still further progress being made, but not so much as the day before. The Germans, who had withdrawn much of their artillery during the bombardment, had pulled it back into prepared positions and within twenty-four hours they began to mow down the advancing waves of our infantry.

During the next four or five days the American infantry suffered bitterly, as the enemy knew their location and used both machine guns and artillery to destroy them. The gains were piece by piece, a few hundred yards each day. Furthermore, they did not have the full support of our artillery behind them, as a heavy rain and the lack of roads delayed the bringing forward of both guns and ammunition. The losses were very heavy, and it was necessary to relieve several of the divisions for rest and replacements. The net result of this first phase of the campaign was that the first two lines of the enemy's fortifications were broken down, he had been forced to draw heavily upon his best divisions in reserve, a considerable wedge had been driven into his lines, and he had lost a good deal of his artillery.

[Photo

at right - "The Advance in the Argonne: Engineers at work repairing

a bridge across the Aire River, which had been dynamited by the Germans

in their retreat."] The second phase of the attack began

with a heavy bombardment along all parts of the line. In spite of

the fact that both light and heavy artillery had been brought forward

into position, the assault met with strong resistance, as the enemy also

had fortified his line with more troops and more machine guns and artillery.

He saw the scope and aim of the drive, and therefore determined

to stop it if possible. He was dug in behind the Kriemhilde Stellung,

a strong line of defense along the heights north of Bantheville, Landres

and St. Juvin. The fighting, under these circumstances, was tooth-and-toenail

for the next three weeks. The American divisions made their progress

almost by yards. Towns and villages were captured, then lost, and

finally recaptured. Every hill or ridge was the scene of bloody

fighting. Abundant aviation was brought into play to photograph

every vital point and to bomb every concentration of troops. Many

of the planes swooped down to the ground and sprayed the trenches with

enfilading machine gun fire. But by the close of October the American

advance had proceeded north of a straight line from Grand Pre to Brieulles.

[Photo

at right - "The Advance in the Argonne: Engineers at work repairing

a bridge across the Aire River, which had been dynamited by the Germans

in their retreat."] The second phase of the attack began

with a heavy bombardment along all parts of the line. In spite of

the fact that both light and heavy artillery had been brought forward

into position, the assault met with strong resistance, as the enemy also

had fortified his line with more troops and more machine guns and artillery.

He saw the scope and aim of the drive, and therefore determined

to stop it if possible. He was dug in behind the Kriemhilde Stellung,

a strong line of defense along the heights north of Bantheville, Landres

and St. Juvin. The fighting, under these circumstances, was tooth-and-toenail

for the next three weeks. The American divisions made their progress

almost by yards. Towns and villages were captured, then lost, and

finally recaptured. Every hill or ridge was the scene of bloody

fighting. Abundant aviation was brought into play to photograph

every vital point and to bomb every concentration of troops. Many

of the planes swooped down to the ground and sprayed the trenches with

enfilading machine gun fire. But by the close of October the American

advance had proceeded north of a straight line from Grand Pre to Brieulles.

The third and final big drive of the campaign was launched on the morning of November 1. Sweeping gains were made that day and they were even more pronounced the day following. The divisions in the center drove a big salient into the heart of the enemy, capturing Buzancy, the German railhead in this region. The flanks also brought up their share of the advance. The enemy, it was apparent, had given up all hope of resistance and relied upon strong rearguards to save his main body from capture by getting across the Meuse first. Learning that his resistance had been broken down, the American forces were driven full speed ahead night and day to intercept the enemy. Trucks were brought up to hasten the advance and wide gains were made daily. The left flank continued the chase northward, while the center and right were swung northeast and east to the Meuse. The first crossing was effected at Brieulles on November 3-4, while other divisions followed and pressed the retreat toward Montmedy to cut the railroad lines there. Meanwhile, the Forty-second Division, which was on the left flank, went forward toward Sedan by leaps and bounds, beating the French there by a day. They held back, however, and permitted the latter to enter first as a matter of sentiment. The main objective had been reached, however, and the German communique of November 8 admitted for the first time in the four years of war that "the German line had been pierced."

When the armistice put a stop to hostilities on November 11, the battle line was completely east of the Meuse, the great four-track railroad line through Sedan and Mezieres, which was the heart of the enemy's lines of communication, had been cut, and the American forces were ready to launch another attack with the First Army in the direction of Longwy and with the Second Army, which was southeast of Verdun, toward Briey and Conflans. These operations, which were sure of success, would have outflanked Metz, the last German stronghold in Lorraine, and made necessary the withdrawal of all the enemy forces across the Rhine into Germany.

But our troops were forced to pay a bloody toll for their success in the Argonne. Twenty-two divisions were used by General Pershing to accomplish his purpose. These divisions were the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 26th, 28th, 29th, 32nd, 33rd, 35th, 37th, 42nd, 77th, 78th, 79th, 80th, 81st, 82nd, 89th, 90th, and 91st. With corps, army, special and replacement troops, about 1,200,000 Americans were directly or indirectly engaged in this great battle. The French used about 140,000 troops for their operations west of the Argonne and also north of Verdun. Against them and our troops were pitted 46 German divisions with a strength of approximately 600,000 men. The American casualties were about 125,000 while the German losses have been estimated at about 100,000.

Other interesting figures which have been compiled in regard to this great campaign of our army are as follows: Maximum penetration of the enemy's lines, 32-1/2 miles; villages and towns liberated, 150; daily average of artillery ammunition fired, 72,541; total artillery ammunition fired during the campaign, 3,408,725; prisoners captured, 316 officers, 15,743 men; material captured, 468 guns, 2864 machine guns, 177 trench mortars.

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Military Page ]

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Main Page ]

Except as noted, all HTML code and graphics in the URL path [http://www.knoxcotn.org/military/wwi/] were created by and copyrighted 2001-2003 to Billie R. McNamara. All rights reserved. Please direct all questions and comments to Ms. McNamara.This page was last updated January 2, 2004. Visitor