The

glamor of the aeroplane drew scores of the young men of Knox County into

its service during the world war. The fascination of the air, the

thrill of spectacular combat high above the battle lines, the prospect

of long flights far into enemy territory, the glory and fame with which

the successful aviator was crowned, made a strong appeal to the young

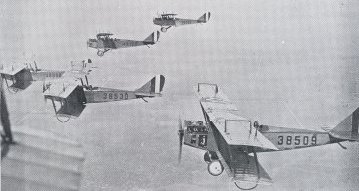

American with strong nerve and hardy constitution. [Photo

at right - "Flying in Formation: These American aeroplanes

are out for a practice spin. The photograph was taken by a member

of the group from another plane."]

The

glamor of the aeroplane drew scores of the young men of Knox County into

its service during the world war. The fascination of the air, the

thrill of spectacular combat high above the battle lines, the prospect

of long flights far into enemy territory, the glory and fame with which

the successful aviator was crowned, made a strong appeal to the young

American with strong nerve and hardy constitution. [Photo

at right - "Flying in Formation: These American aeroplanes

are out for a practice spin. The photograph was taken by a member

of the group from another plane."]

That only two -- Lieut. McGhee Tyson and Lieut. Claude O. Lowe -- lost their lives of the scores of Knox Countians who risked them, either as pilots or as observers, speaks for the safety of this apparently very hazardous branch of the service. Lieut. Tyson, who was in the naval aviation branch, made his sacrifice in a flight off the French coast, while Lieut. Lowe was killed in the smash of his plane at Arcadia, Florida.

While some got across and into action, the majority of the Knox County men in the air service suffered the same misfortune as the larger number of those who enlisted in the air department -- they were still in the United States when the armistice came on November 11, 1918. Some of them were at the port, ready to sail. This failure to reach Europe was no fault of theirs, for statistics show that of the qualified flying officers, less than one in three left the United States. Sufficient service planes had not been produced to equip the flyers who were already in France, not to speak of the thousands on this side who were aching to meet the Huns.

The air program of the United States went through a multitude of vicissitudes, of bright promises and bitter disappointments before it became stabilized and as finally put upon an efficient war basis. Because of the lack of planes, our airmen did not become an active, decisive force in the air until the last two months of the war. When war was declared in April, 1917, the United States government had 55 serviceable planes, all of which were obsolete as compared with foreign models, and entirely unsuited to war conditions. Congress at once appropriated $600,000,000 for our air program. The confident prediction was made through newspapers and magazines that the United States would have 10,000 planes on the battle front in a year, a force sufficient to drive the Germans down and give the allies an overwhelming superiority.

[Photo

at left - "A Crash: An aeroplane at Kelly Field, Texas, comes

to grief at the hands of a cadet aviator, who escaped injury."]

The program, however, received jolt after jolt. German spies

in factories held up quantity production of training planes and ruined

all of a certain model, making its abandonment necessary. Divided

management and a change in directors of the whole air program further

complicated the situation. A great deal of time was necessary in

making tests and fitting the foreign designs to our 12-cylinder Liberty

Motor, which proved our chief contribution to aviation. Difficulty

was encountered in getting out the great quantity of spruce, fir, linen

and other materials that are necessary in the construction of planes.

Due to these and a great number of other difficulties, spring of

1918 came before the kinks in the air program were smoothed out and factories

settled down to turn out planes and engines on a quantity basis.

[Photo

at left - "A Crash: An aeroplane at Kelly Field, Texas, comes

to grief at the hands of a cadet aviator, who escaped injury."]

The program, however, received jolt after jolt. German spies

in factories held up quantity production of training planes and ruined

all of a certain model, making its abandonment necessary. Divided

management and a change in directors of the whole air program further

complicated the situation. A great deal of time was necessary in

making tests and fitting the foreign designs to our 12-cylinder Liberty

Motor, which proved our chief contribution to aviation. Difficulty

was encountered in getting out the great quantity of spruce, fir, linen

and other materials that are necessary in the construction of planes.

Due to these and a great number of other difficulties, spring of

1918 came before the kinks in the air program were smoothed out and factories

settled down to turn out planes and engines on a quantity basis.

After much experimenting and consultation with English and French aviation officials, it was decided to concentrate American production of a quantity scale on four types of machines: (1) the De Havilland observation and bombing plane; (2) the Handley-Page night bomber; (3) the Caproni bomber; (4) the Bristol fighting plane. Only the first was produced in quantity before the end of the war. Equipped with the Liberty Motor, it proved the fastest observation plane on the western front. About 700 were used in actual warfare, nearly 2000 more were in France, and 1100 were being turned out monthly at home when the armistice came. Two new models of planes, the Le Pere two-seater fighter and the Martin bomber, were developed and under tests made better performances than any known machines of their class. Neither was completed nor produced in quantity for use on the front. Liberty motors were manufactured much faster than planes. About 13,500 were accepted from the factories up to the time of the armistice, 4435 of these being shipped overseas for use. The British and French recognized the superiority of this engine and made contracts for large numbers of them.

American

flyers, organized into strictly American squadrons, got their first real

chance on the front in April, 1918, when two observation and one pursuit

group, comprising about 35 planes, were assigned a definite sector. Their

success was so immediate and thorough that the French readily turned over

more planes to the Americans and the sector was widened considerably.

In May, the number of American squadrons was increased to 9; in

June to 14, in July to 15, in August, when the De Havillands began to

arrive from America, to 25; in September to 30; in October to 42, and

in November to 45 complete squadrons. In the early months, all of

our squadrons were equipped with foreign planes, principally French. This

continued until August 10, 1918, when the first American manufactured

planes were put on the front. The supply grew rapidly in the next

three months, and on the day of the armistice 667 of the 2698 planes our

aviators were using were of American construction.

American

flyers, organized into strictly American squadrons, got their first real

chance on the front in April, 1918, when two observation and one pursuit

group, comprising about 35 planes, were assigned a definite sector. Their

success was so immediate and thorough that the French readily turned over

more planes to the Americans and the sector was widened considerably.

In May, the number of American squadrons was increased to 9; in

June to 14, in July to 15, in August, when the De Havillands began to

arrive from America, to 25; in September to 30; in October to 42, and

in November to 45 complete squadrons. In the early months, all of

our squadrons were equipped with foreign planes, principally French. This

continued until August 10, 1918, when the first American manufactured

planes were put on the front. The supply grew rapidly in the next

three months, and on the day of the armistice 667 of the 2698 planes our

aviators were using were of American construction.

The first large air operation in which our squadrons took part was the St. Mihiel attack, for which General Pershing assembled the most formidable air force that was gathered during the war for a battle. French, British and English contributed some of their very best fighting squadrons. Our aviators, who were about one-third of the whole force employed, were organized into 12 pursuit, 12 observation and 3 bombing squadrons. We also had 15 balloon companies in operation. The American supremacy in the air during the two days of the attack was very decided. The enemy planes were kept on the ground largely, while ours went far behind the lines, located the German reserves, spotted ammunition dumps and enemy concentrations, and directed the long range artillery fire.

In

the long struggle of six weeks in the battle of the Argonne Forest, which

followed, American aviation was put to its most severe test. A great

deal of the French and English aviation, which was loaned for the St.

Mihiel operation, was withdrawn for use with their armies, but our increased

production of planes somewhat made up for this loss. There was bitter

fighting for the control of the air. The Germans drew to this front

more than a proportionate amount of their very best planes and pilots.

So vital an attack called forth their very best. Losses were

heavy on both sides, but the enemy got the worst of it by a large edge.

The American bombing, pursuit and observation squadrons did excellent

work, getting far behind the German lines, bombarding day and night their

lines of communication and ammunition dumps, and swooping down to the

attack of any concentration of troops in the rear.

In

the long struggle of six weeks in the battle of the Argonne Forest, which

followed, American aviation was put to its most severe test. A great

deal of the French and English aviation, which was loaned for the St.

Mihiel operation, was withdrawn for use with their armies, but our increased

production of planes somewhat made up for this loss. There was bitter

fighting for the control of the air. The Germans drew to this front

more than a proportionate amount of their very best planes and pilots.

So vital an attack called forth their very best. Losses were

heavy on both sides, but the enemy got the worst of it by a large edge.

The American bombing, pursuit and observation squadrons did excellent

work, getting far behind the German lines, bombarding day and night their

lines of communication and ammunition dumps, and swooping down to the

attack of any concentration of troops in the rear.

The

test of battle showed the individual superiority of the Americans in the

air. The Germans, during the few months which American aviators

participated in the war, brought down 357 of our planes, while our aviators

put 755 of the Hun machines out of commission. On the day of the

armistice, there were 45 American squadrons, 1238 American flying officers

and 740 service planes operated by them on the front. About 2500

flying officers were in reserve, while 7000 others in the United States

lacked but a short specialized course of being equipped for battle duty.

Had the war continued until the spring of 1919, the American air

force in numbers and in equipment would have been far superior to that

of any nation on either side. It would have been independent of

all aid and ready to repay our allies for the generous assistance they

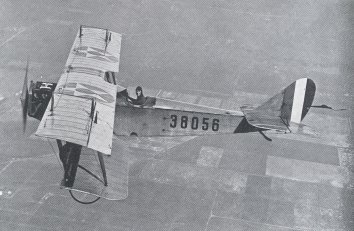

rendered us while our air program was getting under way. [Photo

at right - "A Close-Up View: The photographer who took this

picture at such short range, was in another plane above this one."]

The

test of battle showed the individual superiority of the Americans in the

air. The Germans, during the few months which American aviators

participated in the war, brought down 357 of our planes, while our aviators

put 755 of the Hun machines out of commission. On the day of the

armistice, there were 45 American squadrons, 1238 American flying officers

and 740 service planes operated by them on the front. About 2500

flying officers were in reserve, while 7000 others in the United States

lacked but a short specialized course of being equipped for battle duty.

Had the war continued until the spring of 1919, the American air

force in numbers and in equipment would have been far superior to that

of any nation on either side. It would have been independent of

all aid and ready to repay our allies for the generous assistance they

rendered us while our air program was getting under way. [Photo

at right - "A Close-Up View: The photographer who took this

picture at such short range, was in another plane above this one."]

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Military Page ]

[ Return to Knox County Genealogy Main Page ]

Except as noted, all HTML code and graphics in the URL path [http://www.knoxcotn.org/military/wwi/] were created by and copyrighted 2001-2003 to Billie R. McNamara. All rights reserved. Please direct all questions and comments to Ms. McNamara.This page was last updated January 2, 2004. Visitor